6 July 2020: 8:00 AM (approximately 1 hour)

Join Zoom Meeting:

- Meeting Over

- Meeting ID:

- Password:

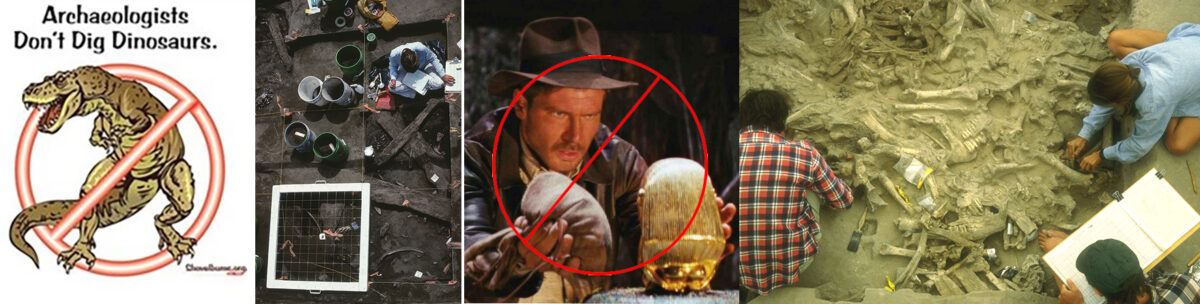

This presentation discusses both what archaeology is and what it’s not. Three common misconceptions are that 1) archaeologists study dinosaurs; 2) archaeology done to collect ancient artifacts; and 3) archaeologists study the past. None of these are entirely true and paint a very distrorted picture of modern archaeology. During this Zoom discussion, we’ll emphasize what archaeologists actually do and why they study the things we do. Have your questions ready!

Activities:

Although this event makes heavy use of on-line resources, there are also things that you can do to help you start thinking like an archaeologist. Some of these include:

- Visit a museum or an archaeological site. There are some suggestions near the bottom of the Science Kids Archaeology 2020 webpage.

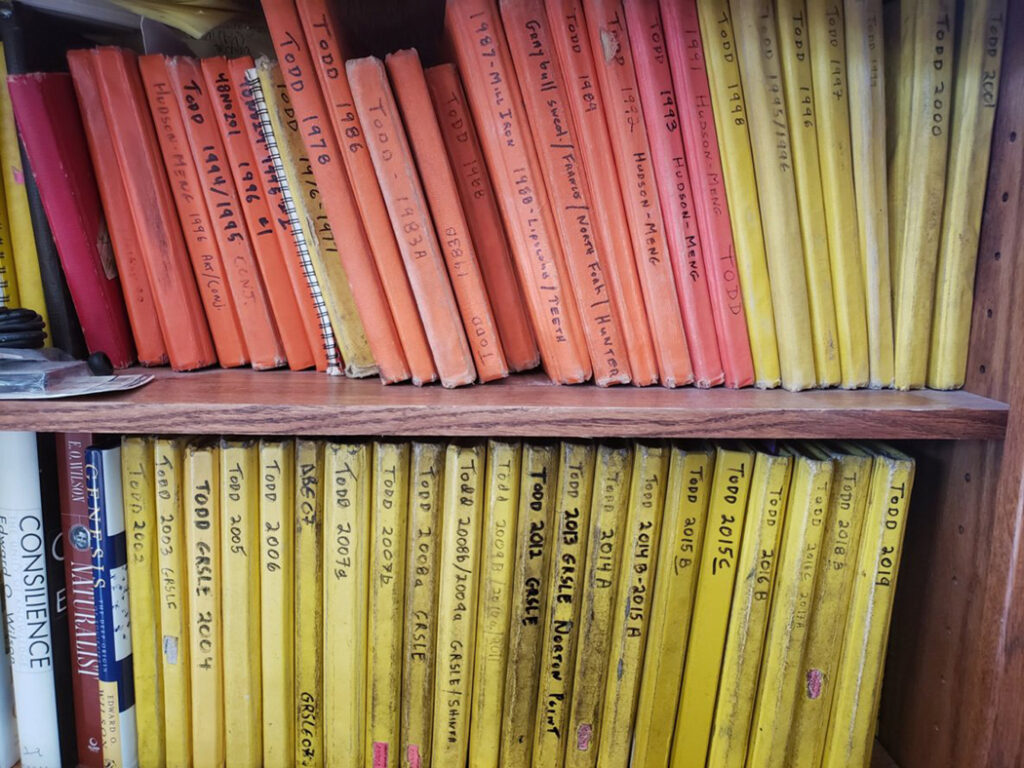

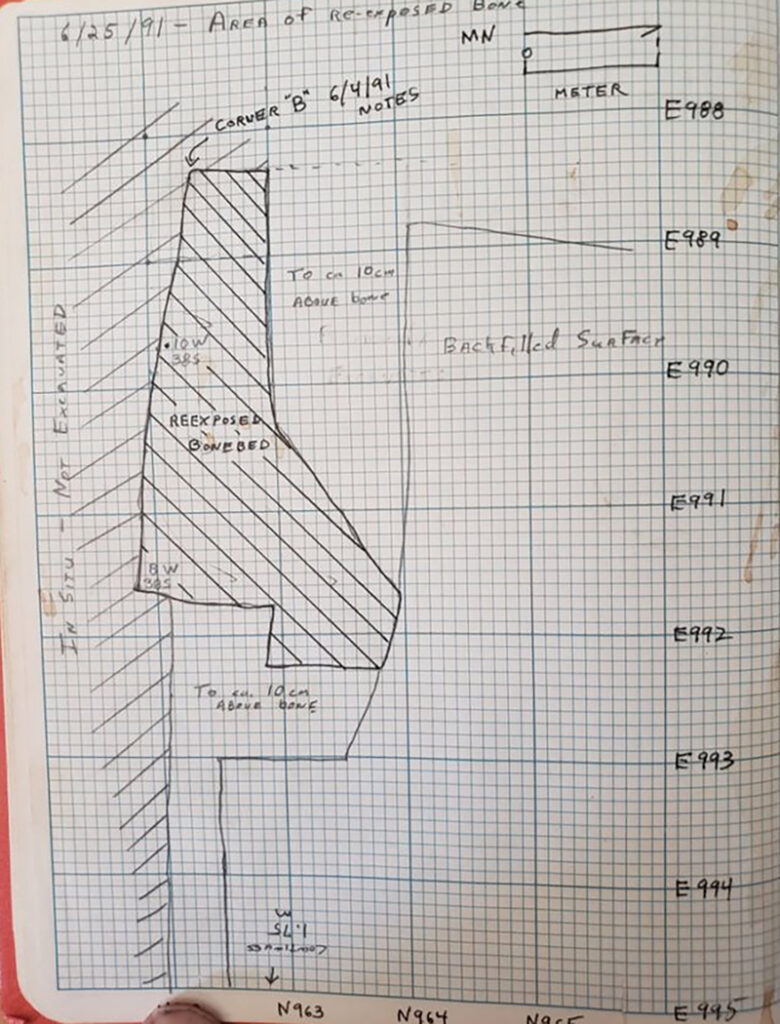

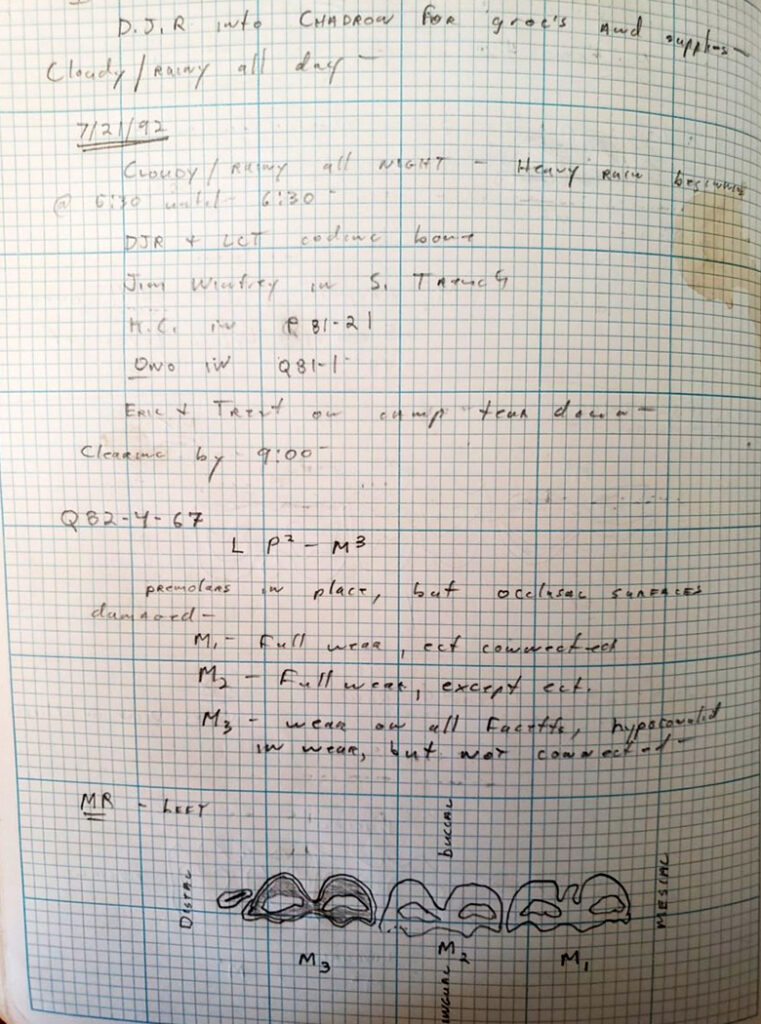

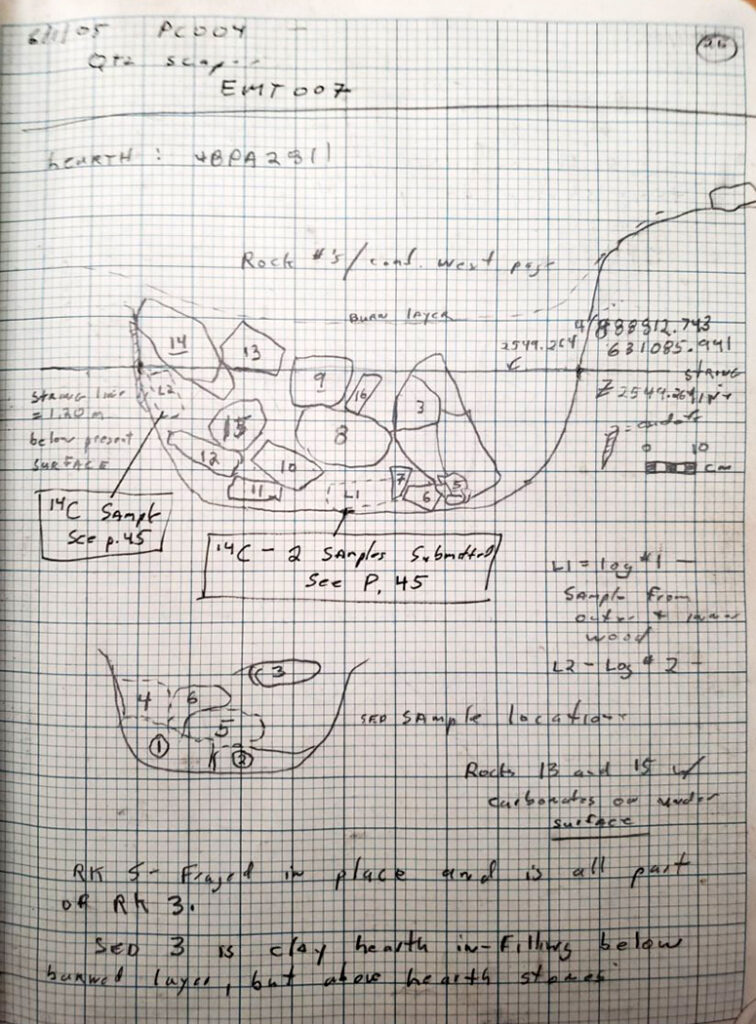

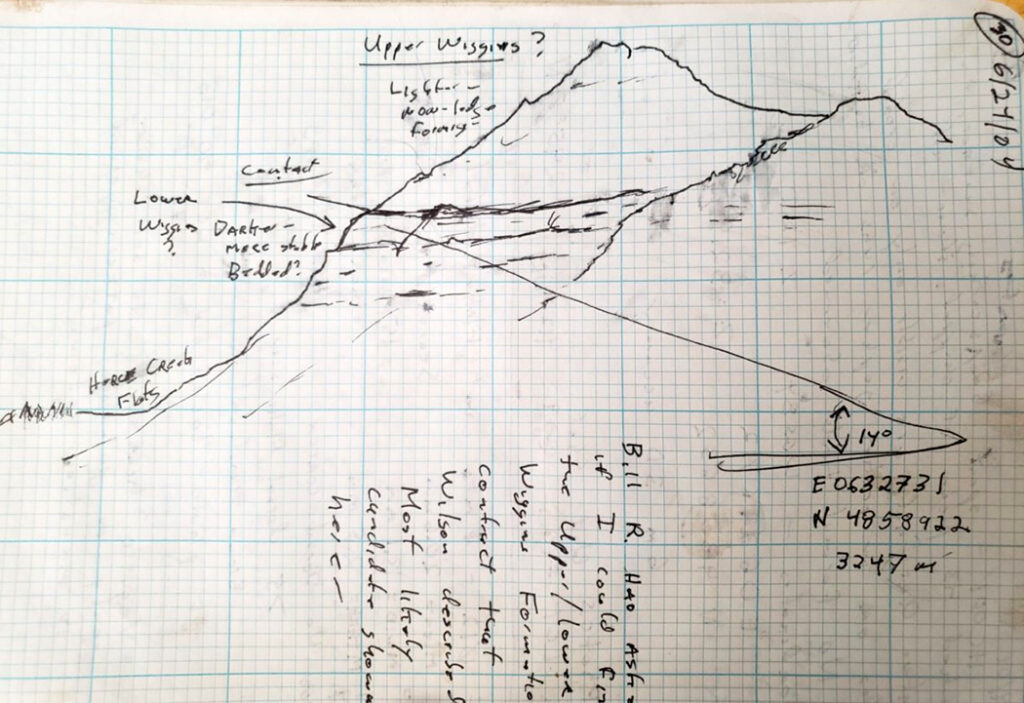

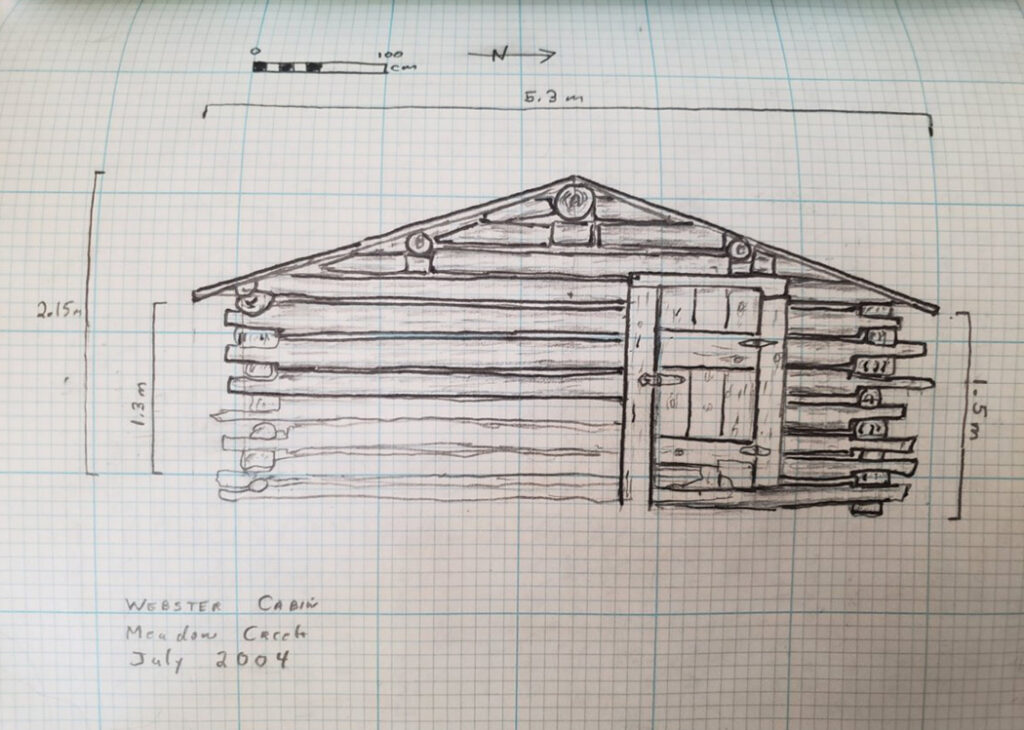

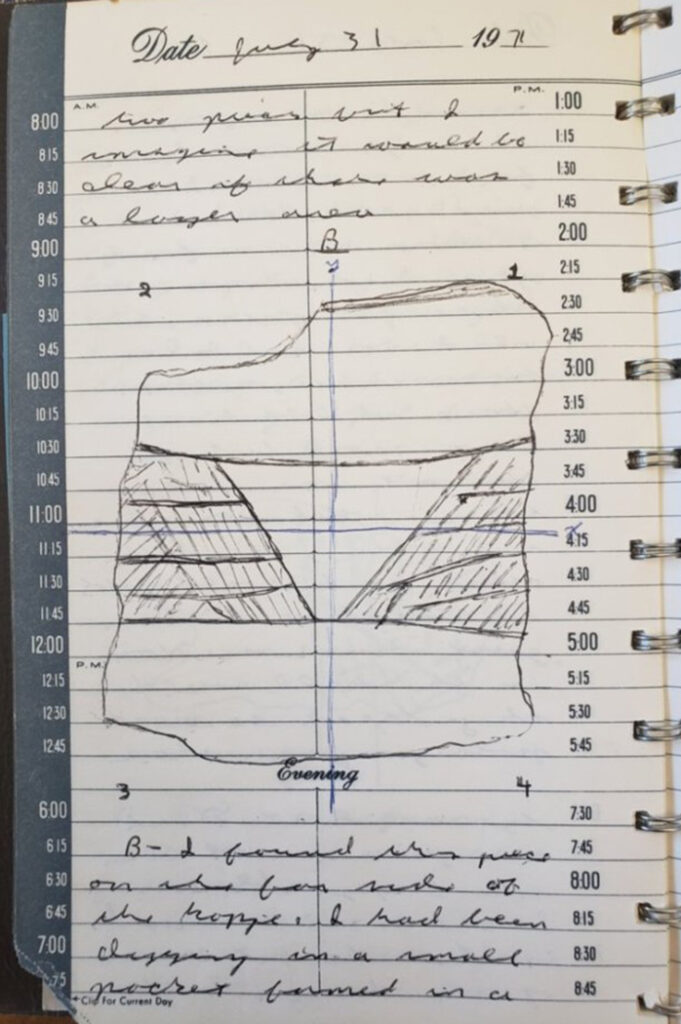

- Start a field notebook and begin recording what you see (examples below).

- Walk around your house and/or neighborhood and identify materials that would likely be preserved in the archaeological record a 1000 years from now, and which might not.

- Make a map of the “site” you live in (e.g., your room, your house), identify what are the main activities that take place there. How would an archaeologist be able to interpret activities from the artifacts found in your site? Think about where something is could help understand what it’s used for — how would knowing that something was next to stove rather than under the television help interpret use? Try to come up with a definition for what archaeologist call context — give examples.

- Try making a replica of a prehistoric perishable (unlikely to be preserved unless in unusual situation like a dry cave or frozen) artifact. The example given uses pipe cleaners to give a feel for the manufacture, but you might want to try making more realistic examples using willow twigs. Think about how many other perishable items used in the past may not have been preserved today. For a look at a more local type of perishable archaeological materials (object preserved in high elevation ice patches), watch the Ice Patch video.

What if you find something?:

Although many people think archaeology is the search for artifacts, we are most interested in what an artifact can tell us rather than in the artifact as a “treasure.” For much of the work we’ve been doing for the last 20 years in NW Wyoming we seldom bring artifacts back — most are recorded and left right where they were found. This does minimal damage to the archaeologial record. What should you do if you and your family are out walking and find a prehistoric artifact? This short video show what an archaeologist would suggest.

We’ll talk about the “Catch and Release” video during our Zoom session, but remember that regardless of opinions about collecting or not, the fact remains that damaging archaeologial or paleontological sites on Federal land (BLM and Forest Service) is illegal.

Field Notes:

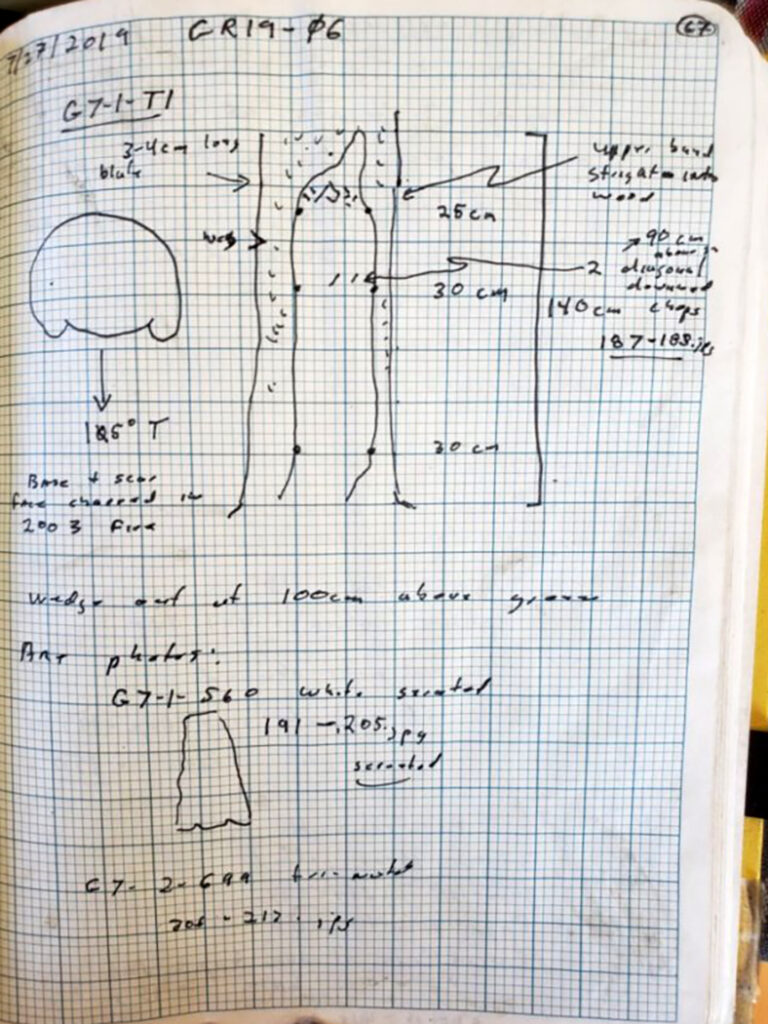

At least as important as what’s found is the information recorded on how, where, when, and what was found. A key part of doing archaeology is learning to systematically and regularly keep detailed notes.

Nearly 50 years of notes

Excavation area plan (1991).

Recording bison teeth in the lab (1995).

Notes on a prehistoric hearth (2005)

Notes on regional geology (2003)

Recording a mountain cabin (2004)

Ceramics from Zimbabwe (1971)

Locations of dendro core samples from scarred tree and projectile point (2019)

DINOSAURS

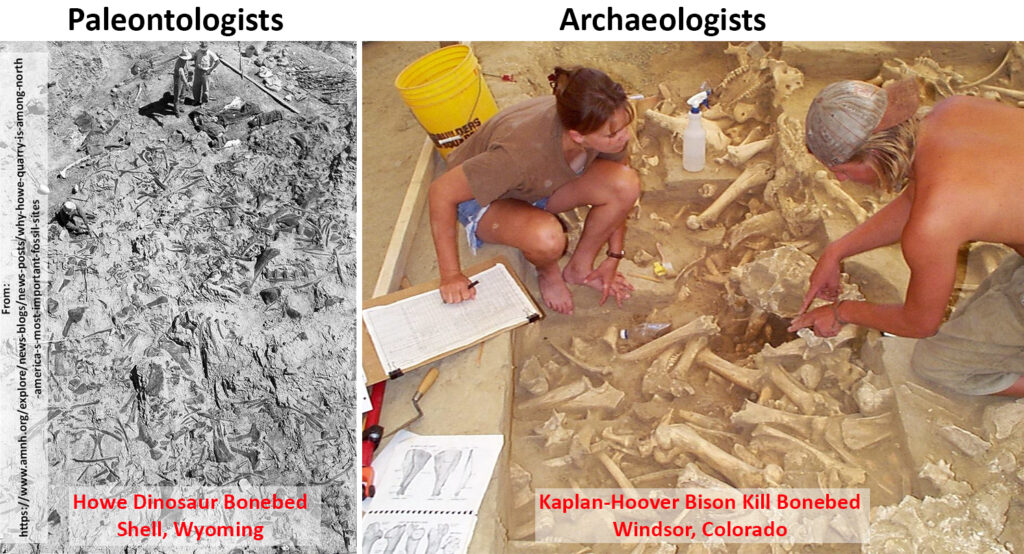

Archaeologists don’t dig dinosaurs. The study of the diversity of earth’s ecosystems, including ancient life such as dinosaurs is a facinating and important research area and archaeologists share many methods with scientists (paleontologists) who can specialize in dinosaur studies. However, the questions archaeologists ask deal with only a limited time and species of interest — we seek information on humans (and human ancestors). Their lives, their diet, their social interactions, their interactions with the worlds they lived in. Archaeologists focus on excavations where there is information about human behaviors. Paleontologists excavate sites to study a much wider range of species (full range of dinosaurs, mammals, birds, reptiles, etc. — the full history of all life). Archaeological research = human research (the deeper understanding of human life).

Read more about archaeological excavations at a bison kill (see why we need to know how to identify bison bones:

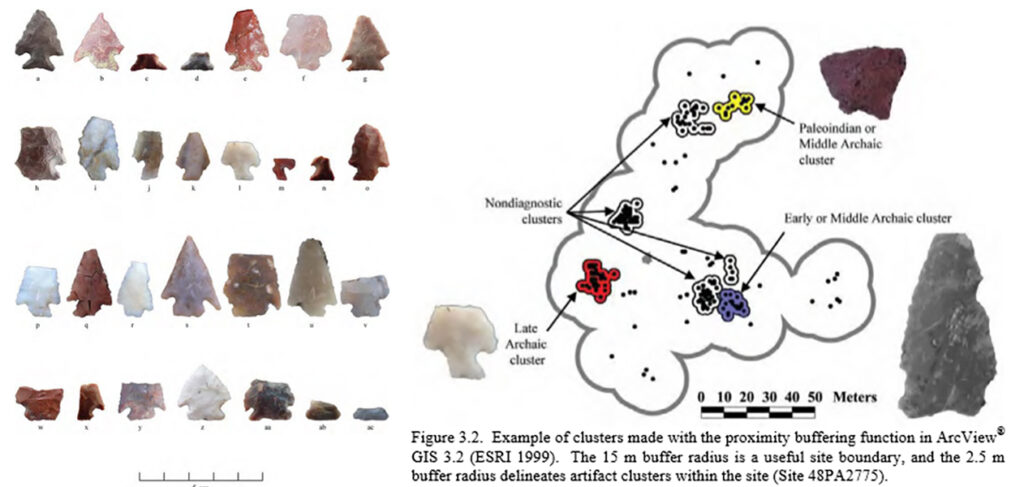

artifacts

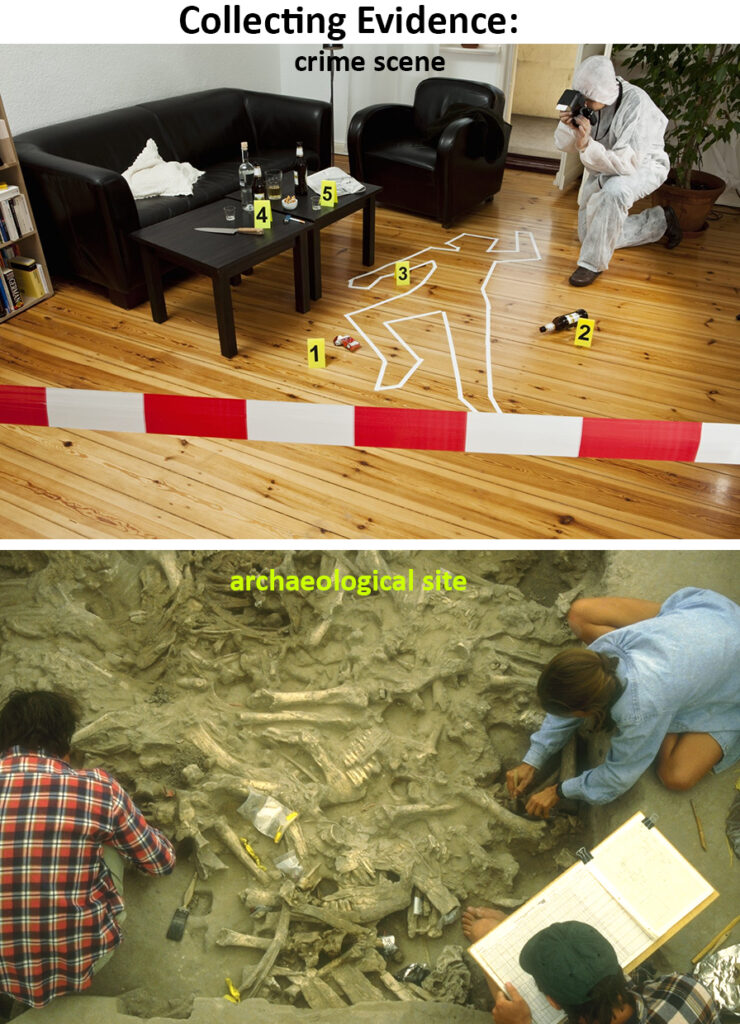

Yes, archaeologists study and sometimes collect artifacts. But collecting artifacts are not the reasons we do archaeology. We use the artifacts as basic evidence to help reconstruct what happened at archaeolgical sites.

Just like on a television show where crime scene technicians collect evidence (such as finger prints, fibers, blood spatter patterns, bullets, et cetera) that help the detectives figure out who committed the crime, the artifacts that archaeologists find and record evidence to help make interpretations about what happened at the site. Artifacts are clues, evidence, data. We don’t do archaeology for the artifacts themselves, we do archaeology to learn from the information they contain.

If an artifact is picked up, taken home (and if on Federal land, stolen), or even just moved from where it was found, it has lost much of its information. Where something is found, and what it’s found with (we call that context) are key to helping develop archaeological interpretation. An artifact may be a very beautiful object, may be a spectacular piece of work, may be really pretty – but without proper context, it can tell us very little about the past. It’s no longer admissible evidence, it’s just an interesting rock. Look at it, record it, and leave it. Artifacts are clues — not treasures or collectables.

the past

While archaeologists work to understand the past, since we don’t have time machines, we can’t study the past directly. We study are archaeological record and make informed inferences about the past. All materials we observe, record, and study are with us here today – in the present. Archaeology is the science that develops and applies methods to make interpretations about the past from these observations made today. That’s one of the reasons we try to protect the archaeological record – it’s the key to help unlock understanding of the past. We ask questions about the past, but can not study the past directly. Have you seen either of the movies that these time machine picture are taken from?

Time machines — don’t have one so can not study the past directly. But what we and do is investigate the archaeological record and make reasoned reconstructions about the past:

What we do

OK, so those are three of the things archaeologist’s don’t do. This series of presentations will give more specific information on some of the things on a few of the things we actually do and just scratches the surface of the range and diversity of archaeological investigations and methods. Have described some of these things above; we sometimes excavate, we collect evidence, we take notes, we work in the laboratory, we write about what we’ve done, we try to expand understanding of the past. As a general structure, here’s an outline of archaeological research – asking questions and seeking answers:

- Make observations on the archaeological record and ask questions about human behaviors.

- Create ideas, models, hypotheses to account for the observations (suggest answers).

- Develop or refine methods to evaluate to your suggested answers.

- Undertake research to apply methods to a body of data.

- Collect new observations/data.

- Evaluate results, see what new questions arise and how you’ll need to re-think your earlier suggested answers.

- Return to step 1 and continue following the research path.

Archaeologist study the archaeological record, which is the remains of the past and their context surviving today, to make inferences about the past. We cannot study the past directly.

Here’s an example of an archaeologist talking about some of what we do, and why:

Listen to recent Meateater podcast about archaeology (2 hours)

Steven Rinella talks with Dr. Lawrence C. Todd and Janis Putelis. Topics discussed: kill sites; the meaning of an artifact; taphonomy: the study of death; possum that took up residence inside of a dead buck; big-assed tongues; Larry’s “it’s not my problem, I’m retired” ethos; humans as the most invasive species; catch and release archaeology; high elevation corridors; the argument against Steve’s argument that people should leave wilderness alone; a child-like curiosity; and more.