8 July 2020: 12:00 noon (apprx. 1 hour)

Join Zoom Meeting:

- Meeting Cancelled.

- Meeting ID:

- Password:

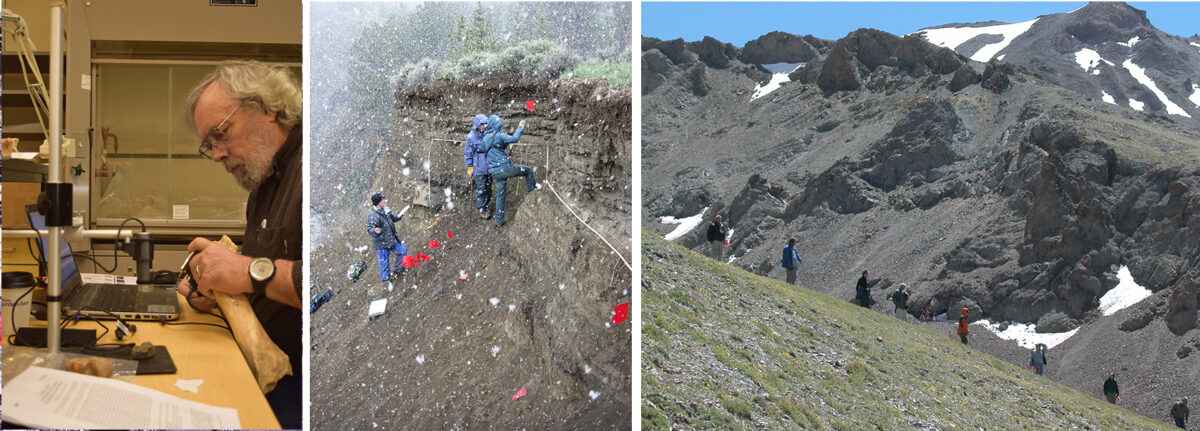

Archaeologists do many different things. Field work, laboratory work, analysis and writing. In the United States, almost all archaeologists are trained as part of Anthropology programs where the goal is to investigate the range of diversity of the human experience. This session will talk about archaeological training, the things archaeologists do and how this relate to other sciences, and answer your questions about archaeology. To give you an idea of what field archaeology can look like in northwest Wyoming, images of work the GRSLE project has done since 2001 are provided below. After fieldwork, much more time is spent in the office and laboratory doing additional analysis and descriptions of what was found in the field. Be aware, that most of these photos deal only with archaeological fieldtime, which in terms of an archaeologist’s work life is usually only a very small proportion — most of our time is spent in laboratory work, writing about what we find, asking for money, and planning for next year’s fieldwork! We do not do archaeology to collect artifacts, we do archaeology to try to get better answers. Questions, methods, ideas about answers are the sparks that ignite new research.

Activities:

- Read and think about the Stadium Showdown Simulation from the Society for American Archaeology education pages. Think about the issues related to historic preservation. What do you think should be given greater value — the past or the future? What do you see as the relative values of preservation versus development? Are they ways to compromise or is it just one or the other?

- Make a list of the types of classes or subjects that you think would be either necessary or useful to study if you wanted to do archaeology. There are many options for archaeologists to specialize. Some study bones, some study tools, some like to excavate, others like to work on computer models. Some are facinated by the very ancient, some by the more recent periods. If you wanted to study archaeology want questions do you think you’d be most interested in?

- Are there jobs in archaeology? Take a look at the Shovel Bums website and click on the Jobs link at top of page. What are the qualifications required for the different sorts of jobs?

- Look at several programs for studying archaeology and what sorts of classes are offered. Here are some programs in the region — look at several (or search for other programs). What are the the similarities and differences?

- Northwest College – Archaeological Technician

- Northwest College – Archaeology Technology

- Central Wyoming College – Anthropology

- University of Wyoming – Anthropology

- Montana State University – Anthropology

- University of Montana – Anthropology

- Colorado State University – Anthropology

GRSLE Project Archaeology NW Wyoming’s Mountains

TRAVEL. Much of the archaeological fieldwork our project has done over the last 20 years has been a long way from the nearest road. Travel in and out of the research areas is sometimes a challenge.

INVENTORY. One of the things we do in the field is systematic inventory — we look systematically examine areas to record the archaeology that’s visible on the surface. Depending on the amount of area we want to inventory, how much time we have, and the crew size we vary the distance apart people walk (called the transect spacing — we usually walk our transects at an average speed of 2km/hour). Not surprising, the closer you look at a landscape, the more archaeology you find.

COVERAGE. For some inventory work, crew members walk across areas at a spacing of about 30 meters apart, which is often called “100%” inventory. This video talks about esperiments about how crew spacing (transect spacing) relates to what you see. There is also a link to an article on this topic below the video.

DOCUMENTATION. Once we’ve found items (mostly stone tools on the surface), we spend a lot of time describing, mapping, and recording information on each item we’ve found. In addition to stone tools we also sometimes record trees, stream invertebrates, vegetation, cabins, and many other aspects of the landscapes were are trying to understand.

IN-FIELD ANALYSIS. Here’s a description of the types of information recorded on every item found. On some sites, there can be thousands of individual pieces recorded like this. Although this video was recorded quite a few years ago, and the mapping equipment we use has changed (GNSS rather than GPS), the basic approach to capturing data on each item on a site is still used:

HUNKERING DOWN. Sometimes the weather is not the best, and the option is to wait a bit so can go back to work (some of the equipment we use does not work in the rain, have to stop for a while):

TAKE A BREAK. We do sometimes take a break, eat lunch, have a snack and maybe sometimes a nap or a shower:

MEALS. Eating in the field is always fun, here are a few shots of a variety of meals over the last few years.

CAMPING. Working in the field often involves spending long blocks of time camping near the area being inventories or near the excavations.

DATA. There’s always a need to add to your field notes and to do other sorts of checking on field records and data.

BONES! In addition to stone artifacts, we also record a lot of animal bones.

TESTING. Most of the GRSLE project work has been surface inventory — just getting an idea of where things are and be plan for what else might be learned from a site. We have done limited test excavations at a few sites.

TEAMWORK. You may have noticed several things looking at these pictures. Archaeologists do many different sorts of things, but most of them require attention to detail and ability to work as part of team. Regardless of whether they are working in the lab or in the field, archaeologists often spend many hours a day recording and analyzing information. It should also be clear that archaeology is a team effort, often involving diverse groups of people (as well as other scientists). Here are some of the teams that have collected data on northwest Wyoming’s prehistory.

Most of the archaeology shown here is study of materials exposed on or near the ground surface, but in many cases systematic excavation is required to answer research questions. Here are some views of a variety of archaeological excavations.

Archaeological Excavations

EXCAVATIONS – OTHER PROJECTS. These photos show a variety of large-scale excavation projects with archaeologists systematically uncovering, recording, and collecting evidences of past ecosystems.

Archaeological Data

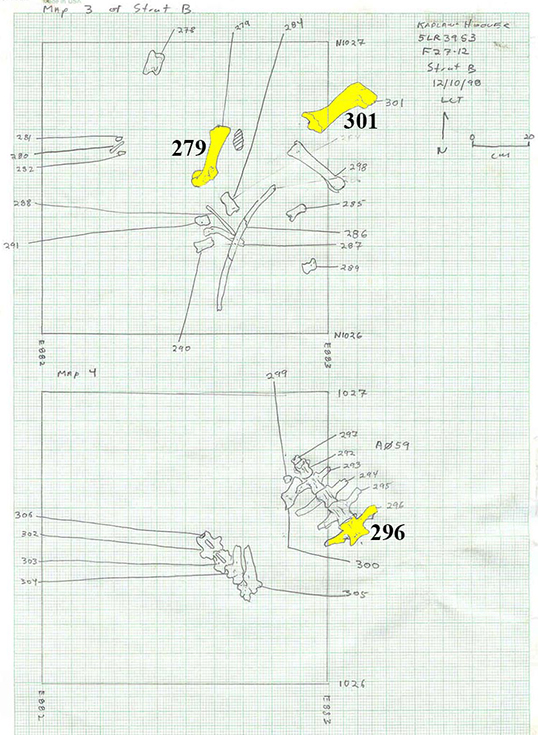

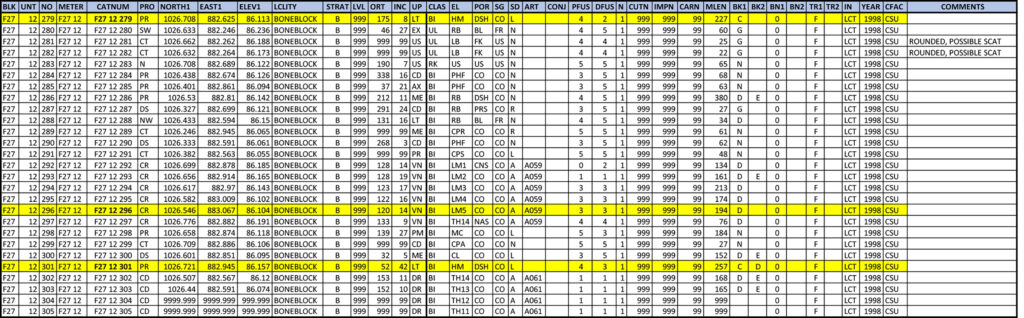

Most of the time an archaeologist is in the field is spent recording things systematically. Earlier in these classes, we’ve talked about a couple things like learning bones, and mapping. As an example of how these two things can be combined when actually doing archaeology, here are two (of hundreds) of maps from excavations at the Kaplan-Hoover site in Colorado (see photos above with more information in the first lesson). The three highlighted bones (279, 296, 301) are also marked in the portion of the site data record in the second image.

And if you really want to ‘dig deeper’ into the types of attributes recorded at a site like this, here’s a link to an Excel file with the codes used to describe each of major attributes recorded at the Hudson-Meng bison bonebed, Nebraska (and at Kaplan-Hoover). There is also more information on some of the types of data collected on arrow and dart points in the Stone Tools lesson.

If you’d like to learn more about archaeology in other areas and from much older sites, take a look at the other research project that Dr. Todd is currently working with in northwestern Ethiopia.

After this Zoom lesson is completed, please take a few minutes and give some of your thoughts on this class. Thank you!